writersnoonereads: No one reads Liliane Giraudon. [The...

No one reads Liliane Giraudon.

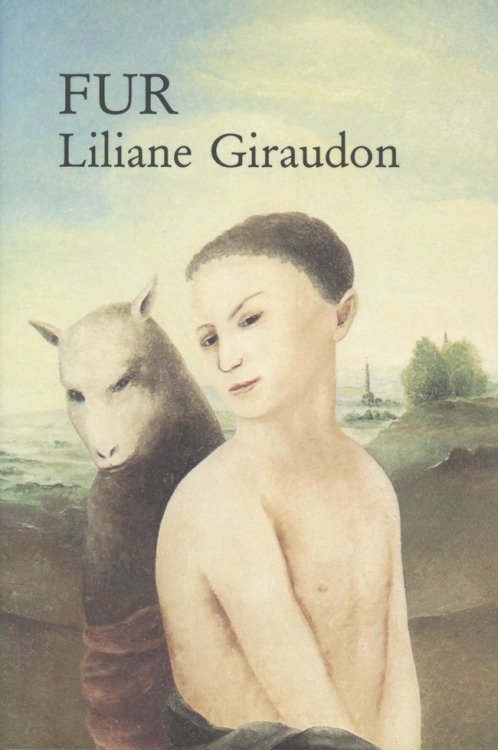

[The following review of Giraudon’s Fur is by Gilbert Alter-Gilbert. It was first published in Bakunin vol 6 (1997) as part of Alter-Gilbert’s feature on the “cruel tale.”]

The first thing that strikes the reader of the fiction of Liliane Giraudon is that she doesn’t write like anyone else. Bearing vague traces of surrealism, Giraudon’s oeuvre draws comparison with that of Leonora Carrington, Gisèle Prassinos, and Rikki Ducornet; but Giraudon is not a surrealist. Neither is she a pure fantast like her French contemporary Julia Verlanger, nor a naive meliorist in spite of all odds like her other compatriot Marie Redonnet [ed.: Alter-Gilbert translated Redonnet’s Dead Man & Company]. Her voice is hypnotic, inscrutable, unique. A trip through one of her narratives is like a somnambular stroll through a rain-soaked ravine with an unreadable road map; a ramble in fugue-state through a wilderness where signposts are written in the language of emotion and the logic of the heart.

Giraudon is a practitioner of silent writing—that is, writing which does not explicitly signal its meaning or purpose. Her poetically-charged prose percolates with unsaid bubblings and unstated gurglings which never surge to the surface, but rush past in irresistible riptides. Her style is discontinuous, at times even fragmentary, yet image-rich and marked by descriptive precision. This disjunctive, highly-colored verbotechny results in an exquisite fuzziness a la Mallarmé. The pieces of her puzzles are like broken mirror shards, each reflecting other parts of a larger image, but never the whole. A clue may be taken from the title of her previous collection of stories (also published by Sun & Moon) Palaksch, Palaksch: a phrase employed by deranged poet Friedrich Holderlin, to mean anything…or nothing.

Giraudon’s operational field is a mythic space unpolluted by references to contemporary cheese culture; her characters breathe the sterile air of psycho-emotional vacuum. Her plots and themes are enigmatic and border on the unreal, if not, at times, the non-representational; but there are badges of familiar sensibility—a preoccupation with victims and victimization, revenge motifs, and acts of unrepentant enmity—conspicuous hallmarks of the cruel tale. Her inventory is stocked with fetish and fixation, aberrant behavior, medical anomaly, atavism, evolutionary warpage, and creatic compulsion. Her characters are wounded souls, lost, lonely, often self-loathing; insular anti-heroes whose private hells slowly unravel to reveal a barely controlled hysteria. Their secret selves, propelled by instinct and animal drives, are awash with dark undercurrents of primal savagery; held in bondage by a sensuality which starts out where D. H. Lawrence left off, they grope in a stew of dream and desire, around which the deformed, the disfigured, and the denatured do a dance for domination. These prisoners of the flesh, beset by strange obsessions, teased by Aeons and Archons, tortured by twisted eroticism, are gripped by predatory forces to which they are tacitly resigned. The spirit of Dr. Moreau is everywhere: hints at moonspawn and mutant progeny abound; insinuations of union between man and beasts accentuate an exploration of biomorphic boundaries and what defines them.

At least two of Fur’s narratives sit squarely in the grand tradition of the cruel tale: “Clothilde’s Goat” and “The Yellow Glove.” Others are about life’s cruelties: its tantalizations and temptations, dashed hopes, and damaged dreams; about dead babies whose absence is commemorated by concluding lines like: “At this time, around her, that is, here, near us, the stars continue their monotonous course; a terrible heart disease is found in all dogs.”

In “Lateral Life,” the subject is bodily sacrifice; in “The Lesson,” interruption, truncation, curtailment of action, inhibition of completion; in “The Peephole,” it is a masochistic ravishment persecution fantasy, with minatory spectral participants; in “The Tie,” the thinness of the veneer separating civilization from the teeming bestiality beneath. In “The Center,” linguistic interpreters inhabit a tactile sensorium which is a metaphor for the elusiveness of the abstract, the unobtainable nature of the absolute, and the ephemerality of all things; “Pauline Buisson” is about the art of suffering, how fate exacts its pound of flesh, how people get under the skin and make each other bleed; in “Wolf Pass” the keynote is the threat of the inhuman; in “Lidia’s Leg,” cross-species loss and longing.

From the country which gave birth to the cruel tale, to the Theater of Cruelty and to Donatien Alphonse de Sade, comes a fresh contribution to the canon of the unkind: Fur is a book of disturbing beauty reverberant with endless mystery.

[Gilbert Alter-Gilbert is a critic, translator, and literary historian whose recent publications include the grim anthology Life and Limb and an English-language edition of Vicente Huidobro’s Manifestos Manifest. An “experimental classicist,” Alter-Gilbert is an inveterate practitioner of fictive history (see Poets Ranked By Beard Weight), a genre pioneered by such illustrious forebears as Marcel Schwob and Raymond Roussel.]

Ed: also see a post on Giraudon on the Project for Innovative Poetry blog.

via Tumblr http://bit.ly/31oHXZa

via Blogger http://bit.ly/2WzIsky

via Tumblr http://bit.ly/2I6n9Ov

Leave a Comment